Introduction

These supplementary materials support ‘God’s Factory’, a play produced for the 3Ai Masters 2021 CPS Stories task. This document provides an introduction to the creative process of our team, key themes in the play, the characters, and our ‘journey’ through the creative process.

Inspiration Starter

We responded to the task brief using the format of a play which enables us a broad exploration of the multi-faceted ideas behind ‘supply/flows’. Our interest was geared towards the limitations and temporary nature of conceptual knowledge as applied to Western constructions of the marketplace and manufacturing throughout human history.

Supply/flows:

- Inspired by… the mis-perception of the 4th industrial revolution that ignores world history up to the 1700s.

- We seek to…look back in time to inform the present and future.

- Our focus…factories as they exist in the CPS of the ‘marketplace’.

What was the creative process behind God’s Factory?

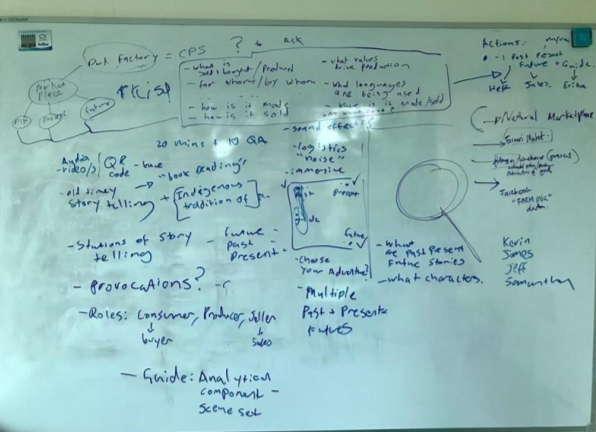

The creative process behind God’s Factory was organic and inspired. Each team member brought a wealth of their own knowledge, understanding and perspectives and together. This contributed to a nuanced and expansive understanding of our inspiration starter. We shared a lot about our own perspectives and spent a lot of time talking to each other, whiteboarding, brainstorming, and iterating.

We made an effort to avoid seizing on our first impressions or ideas of a CPS to ensure we fully explored the provocation of ‘supplies/flows’. We thought broadly about the types of cyber-physical systems that might be explored (including ‘pirates’, ‘goods and services’, ‘religion’, ‘data’). We pivoted along the way in terms of focusing on a CPS, yet each brainstorm session provided us with a wealth of ideas to explore. Some interesting insights included:

- the selling of ‘indulgences’ as a religion-marketplace connection;

- data and identity being sold on the marketplaces of the future (or even identity data being the currencies of the future); linked to ideas of slavery and humans being traded to meet the demands of the marketplace in past (and present);

- privilege and status being demonstrated by spices/tea being from exotic new locations, they were valued because they came from these far away places (e.g. Silk Road) and this being enabled by war, conflict and power.

When it came time to consider the form of our presentation, we sought to lean into the idea of storytelling and actively telling a story. We explored a few versions of what this meant to us and realised that a play was the perfect format to capture the array of insights and perspectives from our ideation sessions and allowed us to weave beautiful layers of complexity into the final work.

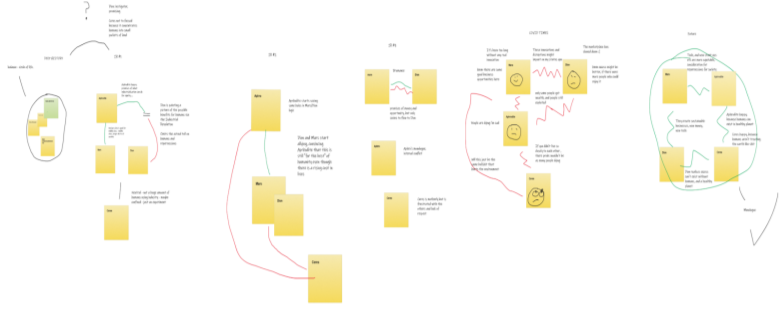

In writing the play, there was a dynamic back and forth process between research and creativity. We drafted monologues for each character which we then worked into conversational exchanges between characters. Key to this process was having a solid grasp of the personalities of each character including their motivations and their way of relating to the world and to each other. We prepared what were effectively ‘character sketches/descriptions’, which allowed us to get to their “core” and explore their perspectives of key historical events in our CPS. We used improv when we were ‘stuck’ writing which helped us translate our percolating ideas about the marketplace into potential conversational exchanges that might occur between the characters.

We wanted to have an accessible and entertaining piece. We included visual and audio aids to the story to enhance the audience experience of the messages and ideas we were hoping to communicate (e.g. the cash register, cows moo-ing, lightning and thunder etc.). We created a soundboard, costumes and physical props, which were then incorporated into the production to add further dimension to the story-telling.

We didn’t rehearse in the space until the evening prior to the presentation. However, it was an incredibly educational exercise for the group and enabled us to explore the ‘physicality’ of the play and further its meaning. There was a noticeable change in the way we understood the play as a group which included negotiating boundaries in how we wanted to demarcate spaces on the ‘stage’. It wasn’t long until we started to experiment in new ways to relate, interact and provoke each other with props as well as the AV material during scenes. This enhanced our understanding of our characters and the narrative arch of the play. On reflection, it was an oversight for us not to move into the physical space sooner. In part, this may have been attributed to some trepidation to actually ‘put on the play’ as it was a new and challenging exercise for all of us!

Finally, we wanted to have a great learning experience as a team and to collaborate with each other in a fun way. We felt like we definitely achieved this!

Themes

Challenging Western Orthodoxy

A key theme was to challenge the orthodoxies of Western theories. We selected a mostly Western/European mythos of the Industrial Revolutions and use these as a vehicle for critique. In the final scene with Cere’s closing monologue, the play seeks to draw out the hyperbolic conclusions of the Western narrative and offer contrasting Indigenous Australian perspectives. During this monologue the character Ceres highlights the narrowness of the perspectives presented through the characters, who are themselves inspired by ancient Greek and Roman gods. The fact that Mars, Dionysius and Aphrodite physically walk out on Ceres as she delivers her closing monologue is an explicit manifestation of this idea. The characters are also dressed in ancient Greek costumes, togas, to provide a juxtaposition to the ‘tech/boardroom’ setting and a ‘way-in’ to demonstrate how the past influences the present while also challenging modern orthodoxy by showing the connective thread to epistemological legacies of the Western canon.

Human and Industrial Waste

Relationships between the environment and waste are embodied by Ceres and her interactions with the other deities. In the opening line, Ceres states that the halt in marketplace activities has enabled the environment to thrive. Moreover the pollution created through manufacturing, industry and waste is reflected in Aphrodite’s interest in ‘evacuating’ humans from Earth and into space.

Waste and excrement is also a natural process of all living creatures, including humans. The play brings back the many technological ways that humans have dealt with waste management throughout time (Japanese toilets, French Bidets, Sewage systems of the ancient Minoans). Moreover, the squabbling over COVID-19 toilet paper shortage illustrates the vagaries between humans/marketplaces and their supply/flows: (e.g. Toilet paper shortage creates a feedback loop in the marketplace > perceived shortage increases the social value of toilet paper > thus demand, influences behaviours like stockpiling which in turn also increased further shortages)

Religion-Spirituality and the Market

Throughout human history, religions and marketplaces have been instrumental in driving significant socio-cultural change. Their related institutions have also been mechanisms for the control and regulation of human behaviours (e.g. Church, W.E.F, multinational corporations). In the play, we wanted to illustrate that a sense of religious ‘faith’ has been transposed into the marketplace as a source of truth. There are many references to the theme. We have called the play “God’s Factory, the main characters are Gods, and there are a total of seven scenes in the play which is significant given that seven is a number appearing several times in the Bible (and the Torah); a nod to this reference in Mars and Cere’s line about Noah’s Ark and the Unicorns. To avoid any religious sensitivities amongst audience members, we made a conscious choice to frame our goods as Greek gods, as they have passed into mythology rather than being actively practiced religions.

Time

We wanted to illustrate how forces or influences from the past still carry over into our present and futures, just reinterpreted over time. We chose not to have a linear progression throughout the play as we wanted to ground our characters to the present day problems for relevance. Given that we were travelling through a long human history, we used flashbacks to explore points in time to put boundaries around the play. We brought the flashbacks in and used their previous motivations and intentions to inform their present. For example, in the flashback regarding the First Industrial Revolution and Aphrodite’s hesitancy in working with Mars and Dionysius in the Second Industrial Revolution. Flashbacks helped anchor and pivot from the present to demonstrate the significant milestones in the development of our CPS – the factory. It also enabled us to interplay the different elements the gods represented in the development of the CPS.

Commercial/Corporate/Start-ups and Tech Culture

The choice of a commercial setting and in particular, a ‘2021’ technology-start-up environment, was for multiple reasons. It was a parody on technology companies and ‘Silicon Valley’ culture of which big technology companies have come to prominence through. Although they have attempted to distinguish themselves from the broader ‘corporate’ legacies, they are still very much part of the same forces of the ‘marketplace’. We chose to deploy commercial/corporate/technology language throughout the play which includes buzzwords such as ‘disruption’ and ‘agile’. The idea of a sprint is also driven by the perceived need to keep up with the demands of the ever changing marketplace. Choosing to put the ‘whole of human history’ into “sprints” and an “agile” framework over iterations brings to light the limitations of short-term problem solving given that the iterations were made over 2000 years.

Characters

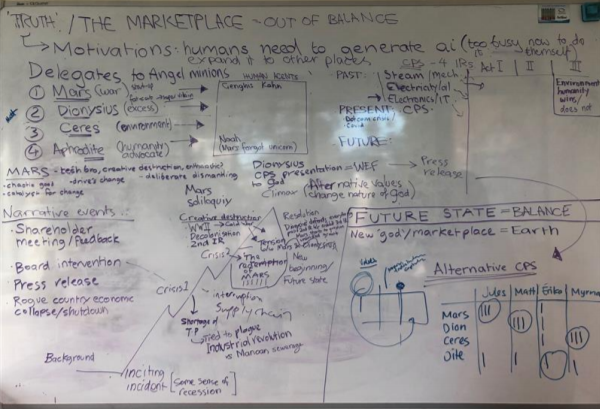

When creating the play, we mapped how the character relationships may have evolved over time (dependent upon the specific forces they represent) according to each ‘sprint’ and expressed at points throughout the play across the last four Industrial Revolutions (IR).

Initially, there is a collaboration between the deities in the first IR, the second IR brings about a collaboration between Mars, Dionysius and an increasingly hesitant Aphrodite. When we ‘fast-forward’ to the present day in the third and fourth IR, we see a breakdown of the relationships between each deity, a tension which is expressed at the start of the play.

Ceres however, remains mostly a constant. Although she agrees with the other characters initially, Ceres grows increasingly frustrated at the other deities as they have neglected the earth and environment. However, Ceres understands that all things return to an equilibrium. She brings her long historical memory of ways that have been in the past into her final closing monologue. Importantly, each character sees things from different perspectives at different time scales.

1. Mars: The Entrepreneur-Inventor. He is a brash, start-up, macho tech guy. He is about 28 years old. Mars is mischievous and fun-loving and thrives on uncertainty, conflict and short-term thrills. He has a creative but destructive temperament. He is constantly seeking new ways to change. Mars is the spirit of innovation. He promises innovation but may sometimes bring unintended consequences. He is prone to short-term thinking. He is bored easily and likes change for the sake of change.

2. Dionysius: The Capitalist. Dionysius is about 45-55 years old who has accumulated massive amounts of wealth. Dionysius jealously guards the wealth he has created and seeks stability and the status quo. He strongly identifies with the idea that he is a self-made man. In the past he might have been a smooth talker and fantastic salesman, however we see less of this these days. He still believes that more is good and that bigger is better. He was ruthless in his work ethic and has been able to deliver incredible projects for god in the last 2000 years and now perhaps, he just wants to enjoy his life. Inside, he is exhausted and the others suspect he might be morally unhinged. Some other defining traits of Dionysius are: “More is good, Bigger is better, Selfish, Expansion is the be all and end all.” He is invested in maintaining the status quo.

3. Ceres: The Environmentalist. The others need her in order to ‘live and play’ on this earth. She is the embodiment of mother nature. She believes in greater responsibility and ‘care’. Ceres is patient, calm and understands that there will always be a state of equal balance, with or without humans. Ceres is a quiet character, who is somewhat ignored by the other characters.

4. Aphrodite: The Humanist. Egalitarian, doesn’t want a polarisation of wealth. She wants as many of her humans to flourish as possible. She truly believes that both humans and gods make mistakes, but often this belief leads her to be complicit to things that do not lead to a better outcome. She was happy to go along with letting the good times roll with Mars and Dionysius, but has been blindsided recently.

Our Journey

From Pirate Cyberpunk brain-dump, our very first session:

To creating the Tasmanian Separatist Sentiment Detection Device during a session with

Mark Thomson using many tools and recycled items:

With Mark Thomson

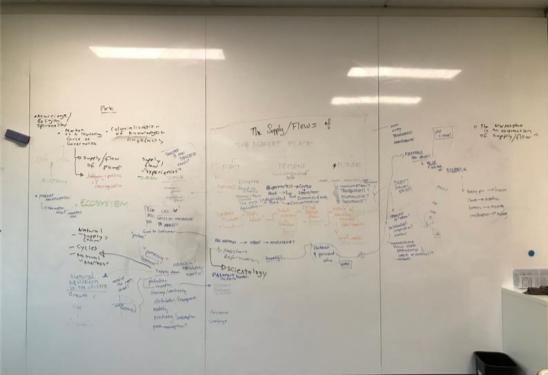

Another board brainstorming session

Being “expressive” throughout the sessions that we have.

Another board brainstorming sessions

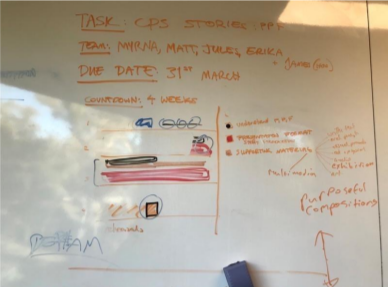

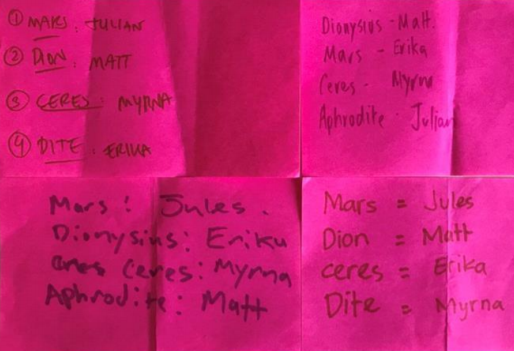

We even took a democratic approach in deciding the role for each one of us to play in one of our whiteboard session

We also brainstormed using an online whiteboard from Teams.

We decided we needed easily accessible sounds for our play, so we created a soundboard:

https://github.com/MattHeffNT/soundboard

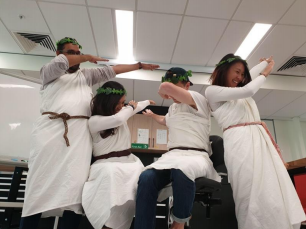

Our costumes for the play, handmade wreaths and half-cut bedsheets

Rehearsing at the studio the day before the presentation.

And the BIG Presentation Day:

We all had so much fun and grateful for the opportunity to work together. Looking forward to our next play again 🙂

Acknowledgement

We the team of Erika, Julian, Matt and Myrna would also like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of James Liu, who assisted with feedback, time keeping, and emotional/moral support.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baptist, E. E. (2016). The Half Has Never Been Told, Basic Books.

Bui, L. (2020). “Asian Roboticism: Connecting Mechanized Labor to the Automation of Work.” Perspectives on Global Development and Technology 19: 16.

Corn, A. (2019). “Friday essay: how Indigenous songs recount deep histories of trade between Australia and Southeast Asia.” Retrieved 9 March 2021, 2021.

CSIRO (2016). Advanced Manufacturing – A Roadmap for unlocking future growth opportunities for Australia. CSIRO.

Eisenach, E. J. (2002). Narrative Power and Liberal Truth: Hobbes, Locke, Bentham and Mill, Rowman & Littlefield.

Emmery, M. (1999). Australian Manufacturing: A Brief History of Industry Policy and Trade Liberalisation. C. a. I. R. G. Economics, Economics, Commerce and Industrial Relations Group. 7.

Forum, W. E. (2020). White Paper – Global Lighthouse Network: Four Durable Shifts for a Great Reset in Manufacturing, World Economic Forum.

Hanlon, W. W. (2019). “Coal Smoke, City Growth and the Costs of the Industrial Revolution.” The Economic Journal 130(626): 26.

Holli Haswell, M. E. L., Signe Wagner (2018). “Maersk and IBM Introduce TradeLens Blockchain Shipping Solution.” IBM New Room. Retrieved 5 March 2021, 2021, from https://newsroom.ibm.com/2018-08-09-Maersk-and-IBM-Introduce-TradeLens-BlockchainShipping-Solution.

Iber, P. (2018). “Worlds Apart – How neoliberalism shapes the global economy and limits the power of democracies.” Retrieved 24 March 2021, 2021.

Kywaymullina, A. (2020). Message from the Ngurra Palya. After Australia. M. M. Ahmad. Australia, Affirm Press.

Long, S. (2002). “Lewis Mumford and Institutional Economics.” Journal of economic issues 36(1): 167-182.

Lupton, D. (2019). “The Internet of Things: Social Dimensions.” Sociology Compass 14(12770).

Metcalf, S. (2017). “Neoliberalism: the idea that swallowed the world.” Retrieved 2 March 2021, 2021.

Mussomeli, A. (2020). “Why smart factories are the future of supply chain resilience.” Retrieved 5 March 20201, 2021, from https://www.supplychaindive.com/news/why-smart-factories-are-thefuture-of-supply-chain-resilience/591752/.

Price, S. (2019). “How Future Factories Will Change Manufacturing – and Supply Chains.” THINK Blog. Retrieved 5 March 2021, 2021, from https://www.ibm.com/blogs/think/2019/02/how-futurefactories-will-change-manufacturing-and-supply-chains/.

Roberts, D. P. (2017). “Revisiting the Mount William Greenstone Quarry: employment specialisation and a market economy in an early contact hunter-gatherer society.” Australian Aboriginal Studies 2: 14 – 26.

Sandemose, J. (2012). “Manufacture and the Transition from Feudalism to Capitalsm.” Science & Society 76(4): 32.

Sandıkcı, Ö. (2018). “Religion and the marketplace: constructing the ‘new’ Muslim consumer.” Religion (London. 1971) 48(3): 453-473.

Schwartz, O. (2019). “Untold History of AI: How Amazon’s Mechanical Turkers Got Squeezed Inside the Machine.” Retrieved 15 March 2021, 2021, from https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-talk/techhistory/dawn-of-electronics/untold-history-of-ai-mechanical-turk-revisited-tktkt.

Snow, R. (2013). I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford, Scribnr.

Sustaiability, G. I. f. (2019). “Data is Just the First Step: The Full Potential of Machine Learning for Advanced Manufacturing.” Retrieved 20 March 2021, 2021, from https://www.rit.edu/gis/coe/news/data-just-first-step-full-potential-machine-learning-advancedmanufacturing.

Toews, R. (2020). “Artificial Intelligence is Driving a Silicon Renaissance.” Retrieved 20 March 2021, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/robtoews/2020/05/10/artificial-intelligence-is-driving-asilicon-renaissance/?sh=2c3b7bc5553c.